War Stories 26

Enjoy the stories in this section. Some of them may even have been true!! Have a favorite war story you've been relating over the years? Well sit down

and shoot us a draft of it. Don't worry, we'll do our best to correct grammar, punctuation, and spelling before we publish it. to us and we'll publish them for all to enjoy.

Medevac Meadow 24-25 May 1970

by

Introduction

This account is written by Gary N. Willis, a forward air controller in

Vietnam using the call sign Red Marker 18. The Red Marker FACs worked

exclusively for the Vietnamese Airborne Division and its American advisors,

members of MACV Advisory Team 162 known as Red Hats. The Red Hats and Red

Markers adopted the uniform of the Airborne -- camouflage fatigues with the

Airborne's unit insignia and a distinctive red beret. That red headgear gave

rise to the American call signs.

)The South Vietnamese Joint General Staff used the Vietnamese Airborne as a

tactical reserve. The JGS ordered Airborne troops into every major battle in

the country, and the Red Hats and Red Markers went with them. In May and

June 1970, the Airborne 3rd Brigade helicopter assaulted into the Fishhook

of Cambodia as part of Task Force Shoemaker. After a few weeks, the Airborne

1st Brigade joined them. "Medevac Meadow" was one engagement that arose

during that incursion. (Comments or questions can be directed to Mr. Willis

at redmarker181969@yahoo.com . He intends to use this description in a

follow-on book to his published history Red Markers, Close Air Support for

the Vietnamese Airborne, 1962 – 1975.

Medevac Meadow1

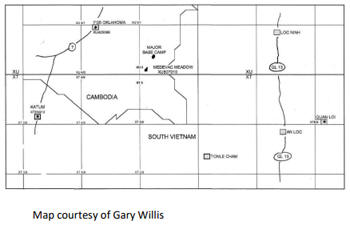

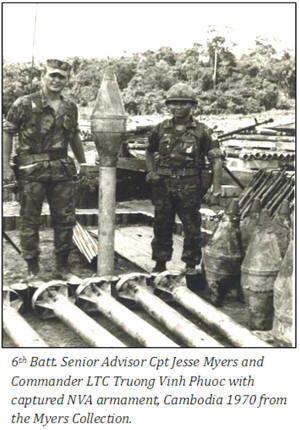

The Vietnamese 6th Airborne Infantry Battalion moved with the rest of the

1st Brigade from Song Be during early May, reinforcing the three battalions

already engaged in the Fishhook. The battalion headquartered at Fire Support

Base (FSB) Oklahoma while its troopers maneuvered in the region. FSB

Oklahoma was about ten miles inside Cambodia off Highway 7 on the eastern

edge of the Memot Rubber Plantation.2 The fire base was the operational home

of the 1st Brigade’s Artillery Battalion of 105 mm howitzers and the long

range 8-inch howitzers of A Battery of the 2nd Battalion, 32nd Field

Artillery Regiment, the “Proud Americans.”

On 23 May, a task force of

the 61st and 63rd Companies of the 6th Battalion encountered NVA troops

during a ground sweep about eight miles southeast of FSB Oklahoma. After a

brief fight, the NVA withdrew to the west side of a clearing oriented

southeast to northwest, and the Airborne retired to the east. The battalion

senior advisor, Red Hat Captain Jesse Myers overhead in a

command-and-control helicopter called for artillery fire from FSB Oklahoma

and asked Red Marker Control to divert some airstrikes to the enemy’s

possible routes of withdrawal.

[1]

The description of the following event is based on numerous

sources, some of which contain conflicting detail: Dust Off: Army

Aeromedical Evacuation in Vietnam by Peter Dorland and James Nanney;

magazine article by then Captain Stephen F. Modica, U.S. Army Aviation

Digest, June 1975; letter written by former Red Hat Major Jesse W. Myers in

response to that article; emails among various surviving participants

including Jerry Granberg and Ralph Jones (artillerymen), Patrick Martin

(Medevac crew chief), Major (R) Jesse Myers, Monty Halcomb (Medevac pilot),

Major (R) George Alexander, former CW2 Paul Garrity, and CW3 (R) Mac Cookson

(Cobra pilots); Oral History and other statements by Warrant Officer Rocco;

mission statements by Alexander and Garrity, by Henry Tuell (Medevac pilot);

various reports of awards and citations/orders related to same; and other

sources as individually footnoted.

[2]

Grid Coordinates XU425098, per the History of the “Proud Americans” at

https://proudamericans.homestead.com/VIETNAM_1963-1971-1.pdf

The artillery fire mission required

extra caution. Only eighty meters separated the NVA on the west side of the

clearing from the Airborne troopers on the east side. The standard safe

distance from an 8-inch round with its 200 pounds of explosive was 100

meters for unsheltered personnel. A miscalculation could prove fatal. The

howitzers’ alignment, elevation, and propellant charge had to be just right.

The fire control center made its calculations and then double checked them.

Then A Battery Commander, Captain Lee Hayden, double checked the “double

check” by hand.3 Myers watched the first shots land on target and gave the

okay to fire for effect.

A Red Marker FAC arrived on scene and

orbited to the east awaiting a set of fighters scrambled from Bien Hoa.

Myers briefed the FAC and shut down the artillery when the fighters arrived.

They bombed and napalmed the western tree line as darkness fell. The

Airborne dug in for the night. Overnight, FSB Oklahoma stood ready if

needed, but only sporadic small arms fire came from the opposite side of the

clearing.

At dawn on the 24th, the NVA attacked in strength. The

Airborne drove them back while suffering several killed and eight seriously

wounded. Myers again called on the artillery at FSB Oklahoma and requested

Red Markers direct some airstrikes on the NVA positions. Red Marker 16,

Lieutenant David G. Blair, already in the air, diverted to the site to

control immediate airstrikes aimed at possible routes of retreat. After the

two Airborne companies secured the area, the Red Hats on the ground, Staff

Sergeants Louis Clason and Michael Philhower, requested Medevac. Myers

relayed the request to Brigade HQ and asked for gunship cover. The request

went out to the 1st Air Cavalry’s Medevac and Blue Max gunship units at

about 1100 hours.4

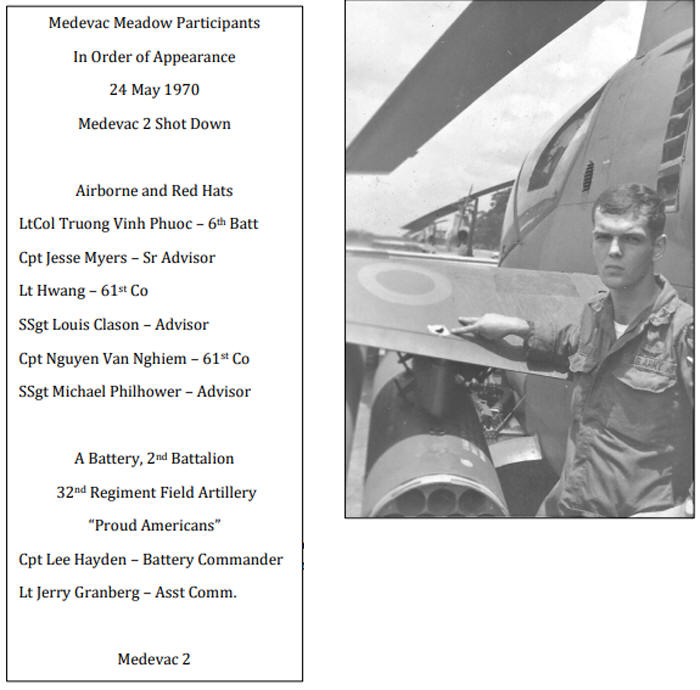

A Medevac helicopter piloted by “The Wild Deuce”

(official call sign Medevac 2), First Lieutenant Stephen F. Modica, and a

pair of Cobra gunships, Precise Swords 12 and 12A, received the requests for

the evacuation mission. Modica was en route from Phuoc Vinh to Katum when he

got the call. Red Hat Sergeant First Class Louis Richard Rocco, happened to

be on board hitching a ride to Katum. Rocco, a qualified medic and advisor

to the Airborne’s Medical Battalion, sometimes volunteered to fly on Medevac

missions. When Rocco heard Medevac 2 was going to pick up wounded

paratroopers, he asked to stay on board and help. Modica landed at Katum,

offloaded some supplies, and picked up a ceramic chest protector for Rocco.

The Wild Deuce departed Katum toward the task force location.

Blue

Max aircraft commanders First Lieutenant George Alexander Jr., Precise Sword

12, and Chief Warrant Officer–2 (CW2) Paul Garrity, Precise Sword 12A, were

on Hot Alert at Quan Loi. They scrambled within the requisite two minutes

from the time the alert horn sounded. Quan Loi Tower clear the flight of two

to take off to the south. As Alexander and Garrity smoothly nosed over and

headed down the runway, CW2 James “Bugs” Moran in the front seat of the lead

ship radioed Blue Max operations on VHF for mission information.

[3]

Emails July 2021, former Lieutenant Jerry Granberg, second in command, A

Battery, 2nddof the 32of the 32nddField Artillery.Field Artillery.

[4]

Medevac Platoon, 155thMedical Battalion, 1Medical Battalion, 1sttAir

Cavalry Division, and C Battery, 2Air

Cavalry Division, and C Battery, 2nddBattalion Aerial Rocket

Artillery, 20Battalion Aerial Rocket

Artillery, 20thhArtillery Regiment, 1Artillery Regiment, 1sttAir Cavalry

Division.Air Cavalry

Division.

“Blue Max Ops, this is Precise Sword One Two airborne on scramble. Mission

brief. Over.”

“Roger, Precise Sword Twelve. Mission is Medevac

escort for pickup at XU5101 in a hot LZ. Depart Quan Loi heading 290

degrees, about seventeen klicks. Rendezvous with Medevac Two coming out of

Katum.”

“Roger, Blue Max. Copy all. Heading 290.”

Precise

Sword flight tuned in Medevac’s standard frequency 33.00 FM and met The Wild

Deuce on the way to the LZ. Meanwhile, Blair returned to Quan Loi for fuel

and rockets while another FAC, most likely Lieutenant Byron Mayberry, Red

Marker 19, arrived on scene with a flight of diverted fighter aircraft.

Myers again shut down the artillery while the Red Marker directed more bombs

into the western tree line. A few minutes after the airstrike finished, the

trio of helicopters was several miles from the clearing. The Red Hats

monitored the Medevac frequency awaiting contact. When Medevac 2 called in,

Myers briefed them on the situation and suggested a run in from the south.

Precise Sword 12 and the Wild Deuce descended to the deck two miles out.

Precise Sword 12 A remained high to cover them both and give directions to

the LZ.

“Medevac 2, hold this heading. I’ve got the clearing in

sight about one klick. I’ve got green smoke on the eastern tree line.”

"Roger, Twelve Alpha. Got it.”

All Hell Broke Loose

The Wild Deuce and Precise Sword 12 came in low and fast just above the

treetops. Modica wanted to give any North Vietnamese gunners only the

briefest glimpse of the helicopter before setting down, loading wounded, and

speeding away.

Red Hat Clason, advisor to the Vietnamese 63rd

Airborne Infantry Company Lieutenant Hwang, stood in the clearing and

watched green colored smoke spew from the smoke grenade he had popped.

Behind the tree line, Philhower, advisor to 61st Company commander Captain

Nguyen Van Nghiem, manned the FM radio. They all heard the distinctive

whup-whup-whup of the Huey’s blades well before it entered the clearing.

Lieutenant Hwang had stretcher bearers waiting outside the tree line

with the seriously wounded troopers. Hwang and Clason waited tensely, hoping

they could load the men without any trouble. Modica brought the ship into

the clearing, lined up on Clason, and expertly flared for touchdown.

Just then, all hell broke loose. AK-47 and .51 caliber machine gun fire

ripped into the cabin from the western tree line. The Cobra gunships

responded immediately. They returned fire with 2.75-inch high explosive and

flechette rockets, miniguns, and 40 mm grenade launchers, hoping to suppress

the enemy fire long enough for Medevac 2 to complete its mission. The low

bird turned hard to the left in front of The Wild Deuce to get lined up on

the source of the fire. The high bird dove straight at the NVA positions

unleashing a salvo of rockets. The Medevac’s door gunners opened up with

their M-60 machine guns. Rocco fired his M-16 out the left door into the

trees. Modica felt two enemy slugs glance off his “chicken plate” chest

protector. At the same time, a third round shattered his left knee. The

Medevac pancaked into the clearing. Copilot Lieutenant Leroy (Lee) G.

Caubarreaux swiveled his head to give Modica some shit for such a bad

landing before realizing Steve was hit. Lee immediately grabbed the

controls. “I’ve got the ship!” he shouted over the intercom. As he pulled

pitch and poured on full power, Caubarreaux jabbed the FM key, shouting now

to the two Cobra gunships, “Precise Swords One Two and One Two Alpha, we are

outta here! Cover us!”

Sergeant Clason hot-footed it out of the

clearing as Medevac 2 spooled up and climbed toward safety. But safety was a

long way off. Coming in hot and low to the clearing made the bird harder to

hit. Liftoff was a different matter. The UH-1H helicopter took time to get

back up to speed and out of the clearing. The NVA gunners got a clear view

of the slow-moving Huey and unleashed everything they had. The entire

western tree line lit up. From the left seat, Modica saw the RPM sliding

past normal minimum and knew they were in trouble. He switched to VHF Guard

channel and broadcast, “The Wild Deuce is going down! XU5101! MAYDAY!

MAYDAY! XU5101!”5

At about 50 feet in the air, gunfire and

aerodynamic stress ripped the tail boom from the ship.6

The Huey spun out of

control, crashing to the ground on its right side. Smoke billowed from the

chopper as the fuel tanks burst into flame. In his C&C chopper, Myers

watched in horror as the Medevac seemed to land, then shot almost straight

up and fell to the ground on its side thrashing briefly like a wounded

insect. He thought at first it had fallen on Clason.

In fact, Clason

was not hurt -- unlike the Medevac crew. Sergeant Gary L. Taylor, right side

door gunner, died on impact, crushed by the aircraft. Medic SP5 Terry T.

Burdette was badly burned and suffered multiple fractures. Crew chief and

left door gunner, Sergeant Patrick Martin, was thrown clear and knocked

unconscious. Rocco was also thrown clear, breaking a wrist and hip. Modica’s

leg was shattered, and Caubarreaux suffered a crushed right shoulder, broken

arm, and back injuries. He was trapped beneath Modica as the ship caught

fire.

Precise Sword 12 lined up at low level to attack the tree line

point blank with flechette rockets. Even before Alexander got lined up, Bugs

Moran in the front seat swiveled the minigun under the Cobra’s chin,

spraying the tree line. Meanwhile, Garrity with his copilot Warrant Officer

(WO) James Nabours rolled in from above and plastered the tree line with

rockets, minigun fire, and 40 mm grenades.7 Both ships took numerous hits,

but the Cobras pressed the attack. At one point, Moran asked George on the

intercom, “Are we gonna die here?” Ignoring the tracers flying past, they

made repeated head on passes into the NVA positions.8

[5] The grid coordinates Modica screamed into the mike designated a

one-kilometer square of territory about five miles inside the Fishhook north

of Tay Ninh Province, South Vietnam. In an article Modica wrote for the

magazine U.S. Army Aviation Digest, he incorrectly stated the coordinates as

XU5606, which is right on the border of Cambodia and Vietnam rather than

five miles inside. Chalk that up to the “Fog of War” and frailty of human

memory. Interestingly, “5606” is the designation of the hydraulic fluid used

in the Huey, which might explain why the number came to Modica’s mind while

writing from memory about five years later. According to the Vietnam

Helicopter Pilots’ Association, XU507010 is the six digit grid coordinate

for the downed Medevac, tail number 69-15121.

[6] Precise Sword 12, Lt Alexander did not see the tail boom break away,

but did notice that the tail rotor was not operating as the Wild Deuce tried

to climb.

When Medevac 2

hit the ground, Sergeant Philhower dropped the radio handset and sprinted

toward the clearing, leaving Captain Myers overhead in the dark. Even

without radio communication, Myers knew the paratroopers and Red Hats would

try to get any survivors out of the downed bird. Lieutenant Hwang

immediately sent a skirmish line of 63rd Company troopers forward to provide

covering fire while Clason and Philhower approached the wreck and the

Vietnamese got their injured away from the landing area and back in the tree

line. The Blue Max gunships kept attacking the NVA positions as the Red Hats

pulled survivors from the burning wreckage and helped them to the friendly

tree line. Lieutenant Alexander noticed that one person getting people out

of the burning Medevac “was not wearing Nomex – very odd for an aircrew.”9

Myers informed FSB Oklahoma about the crisis in the clearing and asked for

more artillery fire. The 8-inchers stepped up their fire on the western tree

line, keeping the NVA’s head down. At one point each weapon had several

rounds in the air at the same time. The enemy did not venture into the

clearing in force.

Failed Rescue Attempts10

Modica’s Mayday call attracted numerous helicopters wanting to

immediately pick up the injured crew and the wounded troopers. Precise Sword

12 escorted the first ship, call sign Killer Spade, as it approached the

field. Intense ground fire erupted, repeatedly hitting the Huey, and Killer

Spade aborted the attempt.11 Meanwhile, back at Quan Loi, Captain Henry

(“Hank”) O. Tuell, III, aircraft commander of Medevac 1, learned that the

Wild Deuce was down. He shouted to his pilot Lieutenant Howard Elliott, who

was in the shower at the time, “Get your butt in gear! We gotta go get

Modica and his crew!” Elliott scrambled into his Nomex flight suit and

boots. Tuell had the Huey cranked when Elliott arrived at the revetment

still dripping soapy water. Medevac 1 approached the clearing from the

south, again escorted by Precise Sword 12, and took ground fire that wounded

Tuell. Elliott took control and flew back to Quan Loi where Hank got medical

attention. Meanwhile, Garrity notified Quan Loi they needed to launch the

Cobra section sitting Blue Alert because this situation was not going to be

resolved any time soon.

7 Another Cobra pilot, WO Brian Russ,

claims to have been flying Precise Sword 12 with Alexander in the front

seat. Aircraft commander Alexander disputes that claim. Cobra commanders

Garrity and Cookson also believe that Russ was not involved in the mission.

8 Rocco’s oral history recorded in 1987 testifies to the volume of fire. The

crew does not believe they would have gotten safely to the tree line without

the protection of the Blue Max Cobras. The damage inflicted on the

helicopters speaks for itself.

9 Statement by George Alexander, in

possession of the author. That person could have been Red Hat Rocco, Clason, or Philhower, who all wore camouflage fatigues. Modica and

Caubbareaux wrote that Rocco pulled then from the wreckage.

10 Details of

the failed rescue attempts are primarily from several sources:

•

Undated document titled “MEDEVAC MEADOW

MISSION FLOWN BY LT. GEORGE ALEXANDER AND CW2 PAUL

GARRITY,” copy in

possession of the author,

•

https://15thmedbnassociation.org/war-stories/medevac-warstories10.aspx#Medevac%20Meadows%20The%20Whole%20Story,

and•

Peter Dorland and James Nanney,

Dust Off: Army Aeromedical Evacuation in

Vietnam, Center of Military

History, United States

Army: Washington, DC, 2008, pp 101-106

•

Statement of Monty Halcomb, copy in

possession of the author.

11 Killer Spade was the unit call sign used by

B Company, 229th Aviation Battalion (Assault Helicopter), part of the 1st

Cavalry

Division

Lieutenant Thomas Read, Medevac 12, and his

copilot Lieutenant Monty Halcomb were in the air 40 miles away northwest of

Song Be when they heard the Mayday call. They sped toward the Fishhook and

soon spotted the smoke rising from Medevac Meadow. They arrived just as

Medevac 1 was taking hits and struggling to get out of the clearing.12 At this

point, Precise Swords 12 and 12A were low on fuel and completely out of

ammo. The relief section of gunships led by CW2 Maurice A. “Mac” Cookson

came on station to support subsequent rescue attempts. Cookson asked

Alexander to mark the enemy position for him. Alexander replied, “No can do.

I’m Winchester.13 Just lower your nose toward that western tree line. The

enemy will mark his position for you.”14 Mac did as suggested, and a stream of

tracers erupted toward his ship, precisely identifying the NVA locations.

Mac responded with flechette rockets trailing their telltale red smoke. The

Precise Sword flight limped their dinged Cobras to Quan Loi where

maintenance grounded Alexander’s bird until they could install a new set of

blades. Alexander pulled a slug from Garrity’s seat and presented it to him

some years later preserved in an epoxy pyramid.

Cookson and his

wingman continued the attack on the NVA while Medevac 12 assessed their

options. Read and Halcomb decided to approach over the friendlies in the

eastern tree line instead of coming in from the south.15 They came in just

over the trees, made a right hand U-turn, and started down fast with their

tail pointed at the NVA tree line. The NVA opened fire from the west and the

north as Medevac 12 reached about 100 feet. The crew heard and felt the ship

taking hits. The Huey began a severe vertical vibration at about fifty feet

from the ground. Read aborted the descent, slowly climbed above the trees,

and called, “Mayday.” He set the wounded bird down in a clearing to the east

and shut down the engine as CWO Raymond Zepp, Medevac 21, arrived on scene.

Monty Halcomb jumped out of the Huey to assess the damage to their plane as

Zepp landed close by to pick up the crew, if needed. Although there were

numerous bullet holes in their ship and major damage to one rotor blade,

Read and Halcomb decided to try to get it back to Quan Loi. They were

successful, just barely. The ship went to the scrap heap a few days later,

slung out under a Chinook.16

Medevac 21 took off from the clearing and

flew back to the Meadow to make a fourth rescue attempt. However, Lieutenant

Caubarreaux ordered him not to try. He said the LZ was too hot and there was

no sense possibly losing another ship and another crew.17 As the day ended,

Medevac had lost three ships, one still smoldering in the Meadow and two

heavily damaged – one that had to be scrapped. The crews of the two damaged

birds had made it back to safety. But the injured crew of Medevac 2 and the

wounded paratroopers would spend the night on the ground with no medical

care except first aid.

Clason and Philhower were awarded the Silver

Star for their actions. Vice President Agnew presented the awards at a

ceremony shortly afterwards. Sergeant First Class Rocco was recognized

several years later for rescuing survivors from the chopper and

administering first aid before he became immobilized from his injuries.18 He

was awarded the Medal of Honor presented by President Gerald Ford in

February 1974. The Medevac pilot and crew also received awards for bravery.

Modica received a Silver Star and Caubarreaux, Taylor (posthumously),

Burdette, and Martin each a Distinguished Flying Cross. Those were not the

only awards conferred, for this engagement was far from over, but

unbelievably, despite braving intense enemy fire in repeated head-on

attacks, the gunship crews received no such awards.19

Jesse Myers knew

what needed to happen next. The two Airborne companies had run into a buzz

saw. But they had given better than they had gotten in return. They had a

good defensive position and overwhelming artillery and air support. The only

thing they did not have was mobility. Ideally, they would pull back and

bring in a B-52 Arc Light mission to pound the enemy. But with the number of

injured on hand, the paratroopers could not easily withdraw. They would not

abandon their wounded, and they could not easily move them. They needed to

hold their position until after a successful evacuation of casualties. Some

of the enemy fire now came from the north and south sides of the clearing.

The NVA may have been attempting to flank the two companies or at least be

in position to score more hits on helicopters they knew would be coming.

Myers adjusted the artillery to compensate.

Airstrikes

That afternoon, the Red Markers diverted more strike aircraft to Medevac

Meadow, where Myers informed them of the expanded targets. For several

hours, fighter aircraft bombed and strafed the enemy-held tree lines on the

north, south, and west sides of the clearing. Red Marker 26, Lieutenant

Lloyd L. Prevett, piloting an O-2A from Phuoc Vinh, flew 4.8 hours, his

longest mission of the war. The twin engine O-2A had a rocket pod of seven

rockets under each wing. During his mission, Prevett expended all fourteen

smoke rockets, one at a time, marking different strike locations around the

perimeter of Medevac Meadow. After running out of Willie Pete, he marked

targets with smoke grenades tossed out of the pilot-side window. Prevett

remembers controlling mostly F-100’s, with at least one flight of A-37’s,

and a few Vietnamese A-1E’s. Prevett recalled:

“One interesting note

is I requested a flight with wall-to-wall nape and 20 mm, figuring it would

be a standard load of snake and nape.20 I was shocked when a flight of two F

-100’s showed up with just nape and 20mm. When I put them in, the nape

uncovered a fortified bunker and of course, no snake to employ. Took care of

that on the next flight. My hat is off to all the fighter pilots that showed

up that day. They put their asses on the line to ensure each and every drop

was right where it was needed. Gives me shivers today thinking about what

everyone did to try and protect the guys on the ground.”21

Lloyd did

not record the number of strikes he directed, but remembers being amazed on

his way back to Phouc Vinh at the amount of grease pencil writing on the

side window. He had scribbled on the plexiglass the standard info for each

flight -- mission number, call sign, number of fighters in the flight,

ordnance load, expected time of arrival on scene, and bomb damage

assessment. Given the number of strikes Prevett controlled, it is a wonder

he saw anything through that window.

The O-2A could fly for more

than six hours if conserving fuel with a lean mixture at cruise power

setting. But directing airstrikes with the mixture rich and power often

“balls to the wall” for almost five hours, Prevett’s O-2 was near minimum

fuel when he landed at Phuoc Vinh. The crew chief refueled and rearmed the

Skymaster, cleaned the inside of the window, and the detailed record of

those strike missions was lost to history.

Radio operator Sergeant

Jim Yeonopolus manned Red Marker Control outside the Airborne Tactical

Operations Center at Quan Loi. He remembers the firefight became more hectic

about 1500, when the FACs called for additional airstrikes. As daylight

faded, the fighting became more intense. Earlier, Red Hat Sergeants John A.

Brubaker and James H. Collier asked Yeonopolus if he would accompany them to

the Meadow and stay on the ground overnight to call in air support if

needed. Jim told them he would be more effective with his full set of radios

at Quan Loi. Brubaker and Collier did not make it into Medevac Meadow.

Until nightfall, Red Markers continued to direct airstrikes into the

enemy positions. Lieutenant Gary Willis, Red Marker 18, in his Bird Dog

controlled two more F-100 flights just before dark. According to Captain

Myers, the Red Markers directed 36 tactical air sorties during two days at

Medevac Meadow. Myers saw one FAC make low passes to drop canisters of water

to the Red Beret troopers who had not been resupplied for two days. Most of

the containers missed the mark or burst upon landing, but some made it into

the perimeter intact. Early the next morning, the Medevac crew chief and

copilot retrieved from the destroyed Huey a few glass bottles of saline

solution that survived the wreck and fire.24

Overnight, artillery

support from Oklahoma became even more important. The NVA attacked the

Airborne position three times during the night and were repulsed each time.

The Proud Americans at Oklahoma responded with precise artillery fire,

sometimes extremely close to the eastern tree line. Many of those gunners

had not slept much during the last 48 hours. The Red Hats also called on

flare ships and Air Force gunships to help defend the Airborne position.

A Rescue Plan

Myers returned to the 6th Battalion’s command post at FSB Oklahoma,

monitoring the situation on the ground via the radio net. At the firebase,

he received a surprise visit from Lieutenant General Michael S. Davison, II

Field Force Commander, who asked simply, “What do you need, Captain?” Myers

replied, “Sir, I need a B-52 strike.” Davison said, “You’ve got it.” The

general left and ordered an Arc Light mission for 1500 hours the next day.

Brigadier General Robert M. Shoemaker flew in later to be briefed on

the situation. Shoemaker was a principal architect of airmobile warfare

concepts and an experienced helicopter pilot. He flew his own command and

control chopper throughout his tour.25 Shoemaker listened to all the

information about the condition of the wounded (there were now about 40

casualties), the resupply situation, and the ability of the troopers to hold

on. He vowed to round up additional resources and return in the morning with

a plan.

Overnight at Quan Loi, the 15th Med and Blue Max created a

plan that met Shoemaker’s approval. The 15th lost so many aircraft damaged

or destroyed the first day, it borrowed several Dust Off Hueys for

non-combat missions.26 That freed up enough Medevac birds to send four on the

rescue – three as primary and one as backup. Blue Max committed six gunships

to the mission, half the entire C Battery fleet.

Early the next day,

Shoemaker flew into FSB Oklahoma to brief the Airborne and the artillery

commanders on the plan. Also attending the briefing were the commander of

the Medevac birds and a major representing Blue Max command, each in his own

helicopter. After a fifteen minute briefing, the three left to rendezvous at

Medevac Meadow with the Hueys and Cobras coming from Quan Loi. An additional

command and control helicopter carried Lieutenant Colonel Truong Vinh Phuoc,

Vietnamese 6th Battalion commander; Battalion Senior Advisor Captain Myers;

Captain Hayden, commander of A Battery, 2nd of the 32nd Field Artillery at

FSB Oklahoma; and the Vietnamese artillery commander. General Shoemaker flew

his own Huey in overall control.27

Beginning at 0930, Red Markers

directed a series of strikes into the perimeter of Medevac Meadow controlled

by the well-bunkered NVA. As the airstrikes ended at 1100, the fleet of

fourteen helicopters arrived on station. According to Myers’s description:28

“The plan was for the LZ to be ringed by Arty fire, friendly troops,

and gunship suppressive fire. After we were airborne, we first adjusted the

Arty. There were two ARVN 105mm How batteries, an ARVN 155 mm How battery,

and the American 8-inch battery.29 The prep was fired and the wood line was

smoked30 and then the extraction was started. Arty fires were not shut down,

but shifted to form a corridor through which the Medevac ships were to fly.

The gunships formed a continuous “daisy chain” whereby suppressive fire was

kept on the area of greatest enemy concentration.”

After the

artillery adjustment, Shoemaker flew his chopper at low level the length of

the field to check the safety of the corridor before clearing the gunships

and Medevac birds to proceed.31 The plan worked almost to perfection. CW2 Mac

Cookson led the flight of six Blue Max Cobras spaced out to keep continuous

fire on the NVA. The three primary Medevacs came in, loaded up and took off

in sequence. The first two made it out of the clearing without any damage.

CW2 Richard Tanner, Medevac 24, came in first and picked up the surviving

crew of Medevac 2 at about 1115. Captain Jack Roden, Medevac 7, landed

second and took off with most of the wounded paratroopers. The third ship,

Medevac 25 commanded by CW2 William Salinger picked up the last few wounded

paratroopers but was hit heavily taking off. His ship sank back to the

ground and caught fire. Before the backup bird flown by CW2 Denny Schmidt,

Medevac 23, and his copilot Monty Halcomb could react, another Huey dropped

into Medevac Meadow beside the burning ship. Salinger and his crew shuttled

the wounded Vietnamese aboard the rescue bird, and they safely exited the

hot LZ. No one knows for sure who flew that unidentified Huey.32

Several days later, General Shoemaker presented “impact” awards to some of

the rescue participants in a ceremony at Bien Hoa Air Base.33 One recipient

was Cobra aircraft commander CW2 Mac Cookson. Mac received a Silver Star for

his contribution to the fight. Nineteen days later, General Shoemaker

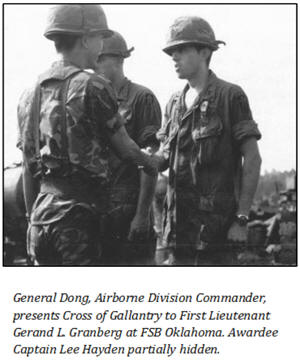

received the same award. At FSB Oklahoma, commander of the Vietnamese

Airborne Division General Dong presented a Cross of Gallantry to Captain

Hayden and to Lieutenant Granberg for the excellent work by their 8-inch

battery. Red Marker Radio Operator Jim Yeonopolus was also awarded a Cross

of Gallantry recognizing his work coordinating strike aircraft for the Red

Marker FACs during the engagement.34

Back in the Fight

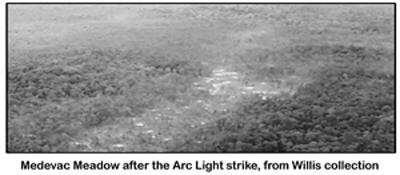

Relieved of their serious casualties, the Airborne companies withdrew a

couple of klicks to the southeast. Resupply choppers soon arrived with food,

water, ammo, and medical supplies. At 1500 hours, the promised Arc Light

mission hit the west side of Medevac Meadow. A light helicopter flew over

later to assess the damage. Surviving NVA drove it off with ground fire but

not before the pilot saw numerous dead and a lot of destroyed concrete

bunkers. While there is no official estimate of enemy casualties, the NVA

must have suffered tremendous losses given the facts. They made four frontal

assaults across the open meadow into the dug-in Airborne position. The

artillery units at FSB Oklahoma poured extremely accurate fire into the NVA

tree line. Air Force fighters bombed and strafed the NVA bunkers with 36

sorties during the two days. Blue Max Cobras flew at least 30 sorties

expending rockets, minigun, and 40 mm grenades into the NVA position. The

B-52 Arc Light mission dropped 81 tons of explosives.

The 61st and

63rd Airborne Companies swept the area the next day capturing weapons,

signal equipment, and some wounded combatants. Some of those were in a

hospital complex. The two companies continued to battle in the Fishhook

until withdrawn with the rest of 6th Battalion on 25 June. At that point,

each company had about 40 effectives remaining of their original 100

troopers. The engagement at Medevac Meadow impressed Myers in a number of

ways, as he wrote in his letter to U.S. Army Aviation Digest:

“I saw

time and again the courage and concern of one pilot on behalf of another. I

saw outstanding teamwork between ARVN and American forces, between air and

ground forces, and between combat and combat support forces. I saw

magnificent employment of air/ground coordination to provide massed fires. I

saw commanders all the way up to the three-star level who were vitally

interested and concerned for the welfare of their men and who were willing

to get personally involved to remedy a bad situation. And finally, I saw raw

courage and heroism displayed time and time again by U.S. and ARVN soldiers

alike.”35

34 Peter Dorland and James Nanney

wrote at page 106 in Dust Off:

Army Aeromedical Evacuation in Vietnam

that nine Silver stars were awarded to pilots

and crewmembers involved in the rescue. I have not been able to confirm that

number. Dorland and Janney did not cite to a record. Unfortunately, both

those men are now deceased.

35 Myers letter.

[ Return To Index ]